write address and affix

write address and affixpostage stamp on reverse side

patakaegonrwinkisch said...

You mean this Cassis De Dijon thingy ? There is something going on, and I must adimt that it has gone off my radar (sorry, but there is just toooo much news out there nowdays). I'll do some research, I'm The Man On The Ground, that's what I'm here for, innit ?

Not just leaving stupid comments with fake silly names and annoying everyone else to leave a comment, but gettin' down to the nitti-gritty, and give somethign back to the blogger community , innit ?

Sun Sep 24, 03:06:55 PM 2006

=============

Fooey. You made me actually have to do research. No, it's not the Cassis de Dijon decision. But thanks for that, I learned lots tonight.

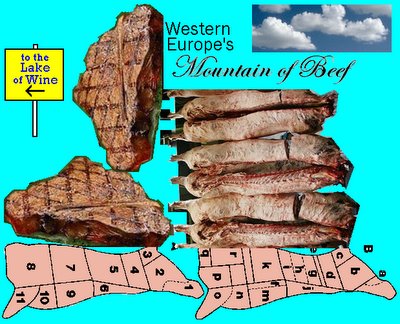

When I visit Europe to see the Lakes of Wine, I'll also get to see the Beef and Butter Mountains! I can't wait to buy postcards and t-shirts and snow globes!!!

They blame the Lake of Wine on CH, you haven't been drinking enough Beaujolais.

~ ~ ~

BBC

Last Updated: Friday, 2 December 2005, 15:35 GMT

Q&A: Common Agricultural Policy

The Common Agricultural Policy is regarded by some as one of the EU's most successful policies, and by others as a scandalous waste of money.

A series of reforms has been carried out in recent years, and the current round of World Trade Organization negotiations could result in further changes.

The CAP has also been a battleground in the dispute over the EU's 2007-13 budget. In the first half of 2005, the UK was demanding guarantees of reduced farm spending before it would agree to cuts in its rebate.

WHAT IS THE CAP?

Agriculture has been one of the flagship areas of European collaboration since the early days of the European Community.

In negotiations on the creation of a Common Market, France insisted on a system of agricultural subsidies as its price for agreeing to free trade in industrial goods.

CAP OBJECTIVES

To increase productivity

To ensure fair living standards for the agricultural community

To stabilise markets

To ensure availability of food

To provide food at reasonable prices

From Treaty of Rome, article 39

The Common Agricultural Policy began operating in 1962, with the Community intervening to buy farm output when the market price fell below an agreed target level.

This helped reduce Europe's reliance on imported food but led before long to over-production, and the creation of "mountains" and "lakes" of surplus food and drink.

Click here to see the beef and butter mountains

The Community also taxed imports and (from the 1970s onward) subsidised agricultural exports. These policies have been damaging for foreign farmers, and made Europe's food prices some of the highest in the world.

European leaders were alarmed at the high cost of the CAP as early as 1967, but radical reform began only in the 1990s.

The aim has been to break the link between subsidies and production, to diversify the rural economy and to respond to consumer demands for safe food, and high standards of animal welfare and environmental protection.

HOW MUCH DOES IT COST?

The cost of the CAP can be measured in two ways: there is the money paid out of the EU budget, and the cost to the consumer of higher food prices.

The EU will spend 49bn euros (£33bn) on agriculture in 2005 (46% of the budget), while the OECD estimates the extra cost of food in 2003 at 55bn euros.

The CAP budget has been falling as a proportion of the total EU budget for many years, as European collaboration has steadily extended into other areas. It has been falling as a proportion of EU GDP since 1985.

EU member states agreed in 2002 that expenditure on agriculture (though not rural development) should be held steady in real terms between 2006 and 2013, despite the admission of 10 new members in 2004.

This means that the money paid to farmers in older member states will begin to decline after 2007. Overall, they will suffer a 5% cut in the 2007-13 period.

If Romania and Bulgaria are paid out of the same budget when they join in 2007 or 2008, that will entail a further cut of 8% or 9%, the Commission says.

Agricultural expenditure declined slightly in 2004, as compared with 2003 but has jumped in 2005 as a result of the admission of 10 new members. Under the European Commission's budget proposals for 2007-13, it will peak in 2008/2009, in nominal terms, then decline until 2013.

WHO GETS THE MONEY?

France is by far the biggest recipient of CAP funds. It received 22% of the total, in 2004.

Spain, Germany and Italy each received between 12% and 15%.

In each case, their share of subsidies was roughly equivalent to their share of EU agricultural output.

Chart showing main beneficiary countries of CAP funds

Ireland and Greece on the other hand received a share of subsidies that was much larger than their share of EU agricultural output - twice as large in Ireland's case.

The subsidies they received amounted to about 1.5% of gross national income, compared to an EU average of 0.5%.

The new member states began receiving CAP subsidies in 2004, but at only 25% of the rate they are paid to the older member states.

However, this rate is slowly rising and will reach equality in 2013. Poland, with 2.5m farmers, is likely then to be a significant recipient of funds.

Most of the CAP money goes to the biggest farmers - large agribusinesses and hereditary landowners.

The sugar company Tate and Lyle was the biggest recipient of CAP funds in the UK in 2005, raking in £127m (186m euro).

It has been calculated that 80% of the funds go to just 20% of EU farmers, while at the other end of the scale, 40% of farmers share just 8% of the funds.

HOW IS THE MONEY SPENT?

Until 1992, most of the CAP budget was spent on price support: farmers were guaranteed a minimum price for their crop - and the more they produced, the bigger the subsidy they received.

The rest was spent on export subsidies - compensation for traders who sold agricultural goods to foreign buyers for less than the price paid to European farmers.

CAP REFORMS

1992: Direct payments and set-aside introduced

1995: Rural development aid phased in

2002: Subsidy ceiling frozen until 2013

2003: Subsidies decoupled from production levels and made dependent on animal welfare and environmental protection

2005: Sugar reform tabled

Q&A: Sugar subsidy reform

But in 1992 the EU began to dismantle the price support system, reducing guaranteed prices and compensating farmers with a "direct payment" less closely related to levels of production.

Cereal farmers were obliged to take a proportion of their land out of cultivation in the "set-aside" programme.

In 1995, the EU also started paying rural development aid, designed to diversify the rural economy and make farms more competitive.

Additional reforms in 2003 and 2004 further "decoupled" subsidies from production levels and linked payments to food safety, animal welfare, and environmental standards.

However, three areas - sugar, wine, fruit and vegetables - have yet to be reformed. Further reform of the dairy sector is planned for the period after 2014.

Rural development funding, which currently accounts for about 13% of the total agriculture budget, is set to increase to 25% before the end of the decade.

In international trade negotiations, the EU has offered to cut all export subsidies, as long as other countries do so too. Big cuts in import tariffs are also being discussed.

WHAT PRODUCTS ARE SUBSIDISED?

The crops initially supported by the CAP reflected the climates of the six founding members (France, Germany, Italy and the Benelux countries).

Chart showing CAP spending

Cereals, beef/veal and dairy products still account for the lion's share of CAP funding, but the southern enlargements of the 1980s brought new crops into the system.

Cotton farmers received 873m euros in 2003, tobacco farmers got 960m euros, and silkworm producers 400,000 euros.

Payments to olive farmers in 2003 (at 2.3bn euros) were larger than those to fruit and vegetable farmers (1.5bn euros), sugar producers (1.3bn euros) or wine producers (1.2bn euros).

Producers of milk and sugar are subject to quotas, which they must not exceed.

Wine is a special case: the EU provides funds to convert surpluses into brandy or fuel - a process known as crisis distillation - and payments to replace poor quality with high quality vines.

HOW MANY PEOPLE BENEFIT?

Critics argue that the CAP costs too much and benefits relatively few people.

BUDGET PRIORITIES (2005)

pie-chart showing breakdown of eu expenditure

How the money is spent

Only 5% of EU citizens - 10 million people - work in agriculture, and the sector generates just 1.6% of EU GDP.

Supporters of the CAP say it guarantees the survival of rural communities - where more than half of EU citizens live - and preserves the traditional appearance of the countryside.

They add that most developed countries provide financial support to farmers, and that without a common policy some EU countries would provide more than others, leading to pressure for trade barriers to be reintroduced.

The importance of farming to the national economy varies from one EU country to another. In Poland, 18% of the population works in agriculture, compared with less than 2% in the UK and Belgium. In Greece, agriculture accounts for more than 5% of GDP, whereas in Sweden the figure is just 0.6%.

The number of people working on farms roughly halved in the 15 older EU member states between 1980 and 2003.

About 2% of farmers leave the industry every year across the EU, though falls of more than 8% were registered between 2002 and 2003 in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and the UK.

At the same time, the average age of farmers is rising. In 2000, more than half of individual farmers in the 15 countries that then made up the EU were aged 55 or over.

Farmers and their employees often work very long hours for little money. Many farms would be unprofitable if EU subsidies were withdrawn.

[Chart showing beef and butter mountains]

==============

BBC

Friday 6 September 2002 08:02 GMT 09:02 UK

France's unwanted wines

Jostling for space - French wines compete with wines from all over the world

by Paul Whitfield in Paris

Travel about twenty minutes north of Lyon, in eastern France, and you'll soon find yourself surrounded by the squat rows of vines that mark out wine country.

Welcome to Beaujolais: a region to warm the heart, and eventually redden the nose, of wine-lovers the world over.

But there is trouble in this paradise.

With all of these regions the high quality wines are doing well, but the cheaper wines are not selling out.

Graham Martin, Wine and Spirit Education Trust

Just as the 2002 harvest is about to begin, the region's wine co-operatives have revealed that they still have a lake of unwanted 2001 wine.

Wine into vinegar

The Union Interprofessionelle des Vins du Beaujolais (UIVB) is an association of wine growers and merchants formed to protect and promote Beaujolais wines.

It said that about 7% of the total 2001 production will have to be destroyed, distilled or sent to vinegar makers.

For anyone who enjoys wine, it is heartbreaking news.

Michelle Rougier, general manager of the UIVB said: "The wine is grade three, the lowest grade. It is being destroyed to preserve the image of the brand and out of respect to the consumer."

That may be true, but the unwanted wine is testament to a bigger problem: production of Beaujolais wines is peaking just as demand falls.

Graham Martin, a teacher at London's Wine and Spirit Education Trust, and a resident of Mille Lamartine in Macon just outside of Beaujolais, said: "The region has lost sales in key markets.

"Some of the more conscientious wine makers are responding by cutting production and increasing quality.

"But others are just grape growers; they are producing right up to their yield limits and shoving it down to the co-ops."

Falling sales

Sales in Germany and Switzerland, traditionally two of the biggest markets for Beaujolais, plummeted by as much as 20% last year.

Much of the decline has resulted from the growing popularity of low-cost eastern European wines, particularly those from Hungary and Bulgaria.

These are wines that compete with the lower end French wines - such as those in the Beaujolais lake.

The news is not all bad for Beaujolais.

Britain is doing its bit for the regions sales.

Beaujolais consumption in the UK was up 26% last year and is already up a further 10.5% over 2002.

French vineyard

This year's crop is also expected to be huge

The US, Japan and Sweden have also bought more wine in recent years.

But these successes have not been enough to offset the lost sales and there is a fear in Beaujolais that after 45 years of growth, the regions' sales may be in long-term decline.

Harvest

For Beaujolais' 4,200 wine makers, the problem is about to be compounded.

The 2002 harvest begins at the end of this week, on 6 and 7 September, and according to the UIVB it will be as big as the 2001 harvest.

Beaujolais' co-operatives are running out of time to get rid of the old wine to make way for the new; raising the likelihood that the wine will be destroyed not sold.

And whatever happens to the 2001 wines there is every chance that the unwanted wine lake will be back again this time next year.

The region's wine-makers are yet to come up with a co-ordinated plan to boost sales and no talk of cutting production is taboo.

Mr Martin said: "Some of the wine makers are taking matters into their own hands. There are some individuals that are actively marketing their labels, others have chosen to harvest only the better grapes and so cut their yields, but there is no concerted effort."

Muscadet and Bordeaux

Unfortunately for France's wine makers the story of Beaujolais' unwanted wine is not isolated.

Other famous wine regions, most notably Muscadet and Bordeaux, are rumoured to be accruing their own stockpiles.

Wine bottles

Wine drinkers are looking to eastern Europe

Mr Martin said: "With all of these regions the high quality wines are doing well, but the cheaper wines are not selling out. They are being overproduced and they are coming under competition from Eastern Europe and, in the case of Bordeaux, Chile and Australia."

Advantage

The UIVB admits overproduction is a problem.

Mr Rougier said that about 50 million to 60 million hectolitres (6.6bn to 8bn bottles) of excess wine is produced throughout the world each year.

"It is a problem for everyone, the competition is harder, but we have advantages.

"Our wine is appellation (government quality certified), so it is very controlled. And we have the Gamay grape which is special to this region. It is a very good advantage if we know how to use it."

Until Beaujolais' growers work that out, it seems the most that we can do is continue to drink generously.

See also:

23 Apr 02 | Business

Chile's wine industry revamps its image

05 Aug 02 | Business

Romania puts sparkle into wine trade

Internet links:

UIVB

Wine and Spirit Education Trust

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites

© BBC

5 comments:

i love stake.

I would visit a lake of wine and sip it dry.

I do love stakes too...they are so delicious....:)

beef stakes are always amazing, i just love the flavors.

This can't have effect in actual fact, that is exactly what I consider.

Post a Comment